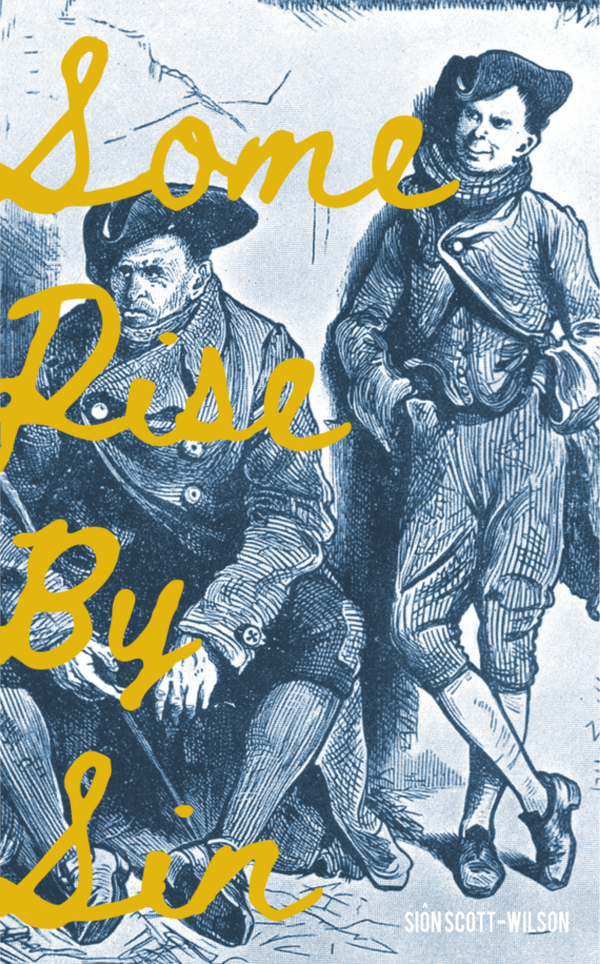

Writer Siôn Scott-Wilson reveals how Edinburgh provided the historical inspiration for his latest novel Some Rise by Sin.

When I left Edinburgh for a while in the late ‘90s to live in New Zealand, we were greeted in Auckland by friends who took us out for dinner at the Old Mission House in Mission bay. ‘This is the oldest occupied building in the country’ they proudly announced. I had not the heart to tell them that the stone shed at the bottom of my garden back in Scotland was a good fifty years more venerable. But then that’s the thing about Edinburgh, wherever you are, you’re never far from a spot of the ancient.

The ‘new’ town is, of course, hardly new. They started building it in 1767 presumably to the chagrin of the ‘old’ town occupants, who must have looked down enviously at the new-fangled buildings whilst marvelling at all the futuristic technology, like glass and plumbing. And shoes.

My father’s family is Scottish, I’m proud to say, and were quite easily traced through parish records all the way back to the 1700s. As it turns out some of my ancestors can be found on a post-Culloden document rendering their oath of allegiance to the crown. If they hadn’t been such lily-livered turncoats, they’d have been exiled and I’d be speaking a completely different language, like Canadian or some such.

Speaking of speaking, I read somewhere that the particular localised accent of Morningside only exists on account of George IV’s walkabout back in 1822, an event ably stage-managed by Sir Walter Scott, who, by leveraging both tartan and the sonsie-faced haggis, more or less single-handedly invented the Scottish tourist industry. At the time, this was the first visit of a reigning monarch in two centuries and so there was, understandably, much excitement. By way of preparation, the upwardly mobile residents of Morningside clubbed together for elocution lessons in an effort to shed their Edinburgh accents. Should Big Georgie come a-calling they could ask whether ‘you’ll have had your tea then, your majesty?’ in a far more genteel tone, employing those distinctive elongated vowels in what was fondly imagined to be an up-market English accent. What I love about this, is that the audible impact of this minor act of snobbery is still very much alive and kicking after all this time. Linguistic historians can still hear it to this very day (but only in Waitrose on Morningside Rd, obviously).

As a writer of historical fiction, there’s no doubt that living in Edinburgh has influenced my work, perhaps even my choice of the period, which is a late regency (my latest novel has been recently described by a reviewer as ‘Regency noir’, which I like very much). But what I think must have been the closest thing to an epiphany was a visit to Mary King’s Close.

This was many years before the venue became a commercial concern and back then few even knew of its existence. For those of you who may not know this is not your average slice of Old Town Edinburgh but an authentic 17th Century close preserved in time. Instead of a new velocipede lane, the council of the day decided to construct a new Royal Exchange and, for that purpose, hoofed all the residents out and built over the top of an entire street, effectively sealing it for a couple of centuries beneath the Royal Mile.

Once below, in the dim and spooky glow of a jury-rigged lighting system, it was possible to see that some of the rooms still retained their original wallpaper. High above one particular chimney breast, we were able to make out a small ragged hole in the brickwork. This, I was informed, was where a child sweep had become stuck up the flue and had to be dragged out, a fairly commonplace incident in those days. It was not known whether he survived. A compelling slice of micro-narrative.

For me, that’s the true fascination of history. All lives are extraordinary, even the smallest ones, perhaps especially those. This is the stuff that interests me and really what I try to write about – the lives of the poor, their loyalties, loves, and struggles to survive in a world which constantly contrives to drive them down. Specifically, I am interested in exploring how individuals might retain a moral compass and essential decency in a fundamentally criminal and immoral environment. To that end my main characters are a pair of bodysnatchers or ‘resurrection men’ as they were more commonly called.

Again, the imprint of this unsavoury activity remains very close to the surface hereabouts. In the mortsafes of Greyfriar’s Kirkyard, for example, and, of course, through the tales of Burke and Hare. Arguably the nation’s most notorious body snatchers, the pair were active in Edinburgh throughout 1828. Unwisely, Burke and Hare, rather than waiting on natural causes to provide corpses chose to lend nature a helping hand. The hand in question, invariably clasping a pillow, was used to suffocate the victims.

Burke was scragged at the Lawnmarket and publicly dissected after Hare turned king’s evidence. His skin was later turned into a notebook, from which we derive the expression ‘never judge a book by its cover.’

William Hare is said to have returned to his native Ireland where he was recognised by a pack of mechanics (the old word for labourers and not, as you might think, sedan chair repairmen) who duffed him up a bit and flung him into a lime pit (caustic calcium oxide not the citrus fruit). Since his later whereabouts are unknown I have him make an appearance in my novel, begging on the London streets. So, like his partner, he also ended up in a book.

Anyway, the Burke and Hare pub has been around for as long as I can remember. However, these days it’s billed as one of Edinburgh’s ‘best strip bars’. Not easy to see the connection here and I had to think about this before it all became clear to me.

Back in the nineteenth-century penalties for theft of property were far more severe than for the theft of a corpse, so resurrectionists would generally strip the bodies bare, leaving behind the shrouds, shifts, garter belts, basques and so forth. So, there you are. Mystery solved.

Incidentally, a quick Google search of the Burke and Hare strip/lap dancing bar reveals that there’s ‘no takeaway’ and ‘no delivery’. So that’s you told.

*not true, probably